You used to call me on my cell phone

Late night when you need my love

What makes a hit a hit?

Since the dawn of popular music, two factors have mattered most, as reporter Derek Thompson explains in Hit Makers. A catchy song. Frequency of exposure.

There’s some science to prove this. iHeart Media owns a songtesting company called HitPredictor. They play hooks from songs to an online panel three times and the audience score the song. Songs can score into the 100s but any score above 65 is considered a potential hit.

Some of the biggest songs score well under 80. Beating songs that score in the 80s, 90s and 100s.

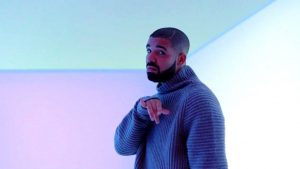

Drake’s “Hotline Bling” quoted above barely scraped 70 in the HitPredictor ratings, but was top five in the Billboard Hot 100 on release.

Songs become hits because if they’re catchy and have a good melody. They also need frequency of exposure.

Pop songs become hits when they’re familiar enough, both in their structure in general (people like something that sounds like something else that they liked) and when the specific song has had enough airplay or online exposure to be recognised.

This is of course not just true of pop songs. The Mona Lisa is the most famous painting in the world. Some argue that this is down to the incident in 1911 when it was famously stolen. This gave the painting immediate notoriety and exposure and as soon as it was recovered, two years later, queues of people lined up to see it, and are still doing so.

And of course this is why frequency matters in media. It’s not just that shared experiences are crucial. It is also that the more familiar we get with a brand (and its brand story), the more likely we are to buy it again.

Data analysis can now pinpoint the precise frequency that is optimal for a brand’s message. Frequency works (although as we know precisely only up to a point.)

Frequency works because it makes the brand easy to think of. Thinking that feels easy is called “fluency”. As Thompson writes: “Fluent ideas and products are processed faster and they make us feel better – not just about ideas and products we confront, but also about ourselves. Most people generally prefer ideas that they already agree with, images that are easy to discern, stories that are easy to relate to and puzzles that are easy to solve.”

Fluency lifts the brand from system 2 thinking (which is hard) to system 1 thinking (which is instinctive).

So frequency is good. But it is not infinitely good. Human beings like new things too. As we develop from babies we learn to love to operate in the zone of proximal development. Just outside our core comfort zone. Where stuff is new, but not too new. Different but sort of familiar. This is an educational term, but it can be useful as a concept for understanding why variations on a theme are so necessary, in marketing as well as in hit making in general.

When catchy tunes start to annoy you, when politicians bore you with the same buzzwords and when yet one more advert follows current trends slavishly then you need the new.

Audiences like the familiar, and they also like the welcome surprise. In media planning repetition is good, but frequency caps are crucial. In marketing sticking to the brand truth is crucial, but regularly surprising and delighting the audience is essential.